Static Sites Are Awesome

When creating landing pages, content sites, or blogs, content management systems shouldn’t be the first tool web developers reach for. Because of the many benefits that come with the simplicity of static sites, they are not only a viable alternative, they are a more practical alternative. And with the popularity of static site generators rapidly on the rise, creating and maintaining static websites is easier than ever.

Why static sites?

For certain types of content, static websites excel over content management systems in lots of areas, including performance, decreased server maintenance, site maintainability, and capacity for version-controlled content.

Performance

In today’s world where site performance is of utmost importance, the most compelling reason to move toward static websites is the performance benefit. Content management systems make use of a database, and reading from the database to serve page content incurs a performance cost. Static sites make no use of a database—all the content is baked right into the final HTML code. The performance win comes from the fact that modern webservers (like Apache or nginx) are heavily optimized to serve such static files extremely quickly.

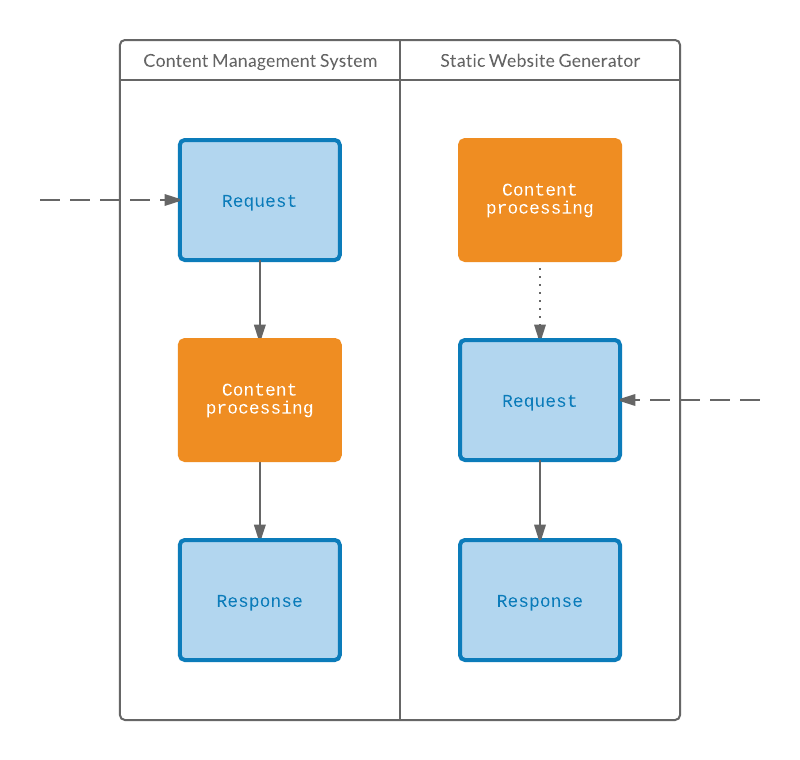

In a nutshell, with a CMS, the burden of constructing a web page is placed on the server, at the time the page is requested. With a static site, that burden is moved to when the site is assembled before it is deployed. Many programmers will agree that, from a user experience perspective, it is better to have as much processing occur as possible at compile time rather than at run time. This is the approach that static site generators take.

Server maintenance

Another big advantage for static sites is the reduced amount of required server maintenance. With a typical CMS like Wordpress or Drupal, sysadmins will need to install and configure a scripting language runtime (like PHP), a webserver (like Apache), and a database server (like MySQL). Security patches and periodic software updates will also need to be run for each of these. With static sites, only a webserver to serve the static files is required. (It is also arguable that security of the server is improved with this simpler setup.)

Maintainability

Some scoff at the idea of building a static website because it sounds to the unfamiliar ear like writing static webpages individually by hand, which of course is a cumbersome task that content management systems were designed to overcome. However, the “static” part is simply the compile target. Static site generators allow web developers to build sites with familiar programming constructs, like DRY, logic and flow control, templating, etc.

Version control

Without the dependency on a database system, it is also much easier to keep the site’s content under revision control, depending on how the developer has chosen to deploy and publish to the site. This also means that content is more easily synced with code between different environments (i.e., development and production).

Concerns with static sites

The obvious concern with static sites is that they cannot serve dynamic content. However, there are ways to add common dynamic elements to the site without the need of a full-blown CMS. For example, the popular service Disqus provides a fully featured commenting system for a page, simply by adding a small JavaScript snippet. There are also services like Firebase that allow client-side applications to communicate directly with a database.

There are, of course, many cases where a static site is inappropriate. Any service where users log in to access their content is a common example. In these cases, one might consider using a static site for blogs or landing pages and minimize the the scope of the backend code to the core of the application itself.

Deploying and publishing content to static sites

Static sites can be deployed in a variety of ways. One of the simplest ways is to take the compiled output of the static site generator and drop it into an Amazon S3 bucket. As S3 (and similar services) are preconfigured to serve static files, there is no server setup required. Take one more step to put that bucket behind a service like Amazon CloudFront, and the site’s files are now served over CDN, with minimal effort!

Another noteworthy mechanism that works great for open-source sites is GitHub Pages, a free service offered by GitHub. GitHub Pages integrates automatically with one of the most popular static site generators, Jekyll, and so deploying and pushing updates to a site is as simple as git push. GitHub Pages are also served via CDN.

There are also great workflows that allow non-technical people to publish to a static site. For example, Contentful is a content management service that has fast, read-only APIs for retrieving content. Non-tech writers can log into Contentful to create the content, and the static site generator could be configured to receive updates from the API, compile the site, and deploy the changes automatically. A similar workflow based on syncing a Dropbox folder of markdown files with a static site generator could also work well. With the flexibility of static sites, teams can find a publishing paradigm that works well for them.

Conclusion

Static websites are a practical tool in a web developer’s tool belt. The simplicity of a static website can be a welcome replacement for complex content management systems.